Concert Preview

Trumpeter Roditi returns

March 16

for

another BMF concert in Lincoln

By

Tom Ineck

Early in its history, the Berman Music Foundation took an

interest in trumpeter Claudio Roditi, bringing him to Lincoln for a performance with

saxophonist Greg Abate in February 1996. The concert at the

now-defunct 7th Street Loft also featured pianist Phil DeGreg,

bassist Bob Bowman and drummer Todd Strait, all of whom have

maintained close ties with the BMF.

Claudio Roditi, bringing him to Lincoln for a performance with

saxophonist Greg Abate in February 1996. The concert at the

now-defunct 7th Street Loft also featured pianist Phil DeGreg,

bassist Bob Bowman and drummer Todd Strait, all of whom have

maintained close ties with the BMF.

Roditi returns to Lincoln March 16 as guest soloist with the

Nebraska Jazz Orchestra at the Cornhusker Hotel ballroom, a

performance again sponsored by the BMF. Roditi may not receive the

worldwide recognition he so richly deserves, but he has friends and

supporters in the Heartland.

Referred to as the Kenny Dorham of the 1990s, Roditi has an

exciting edge in his neo hardbop approach. Born in Rio De Janeiro,

Brazil, in 1946, he began playing piano as a child, but turned to

the trumpet at the age of 12. Listening to records by Harry James,

Louis Armstrong, Red Nichols and others, he began mixing jazz with

his native music, during the 1960s bossa nova boom.

He moved to the United States in 1970 to study at the Berklee

College of Music in Boston, where he picked up an occasional gig

until moving to New York in 1976.

Among other leaders who called on him were saxophonists Charlie

Rouse and Joe Henderson, flutist Herbie Mann, percussionist Tito

Puente and pianist McCoy Tyner, but it was his relationship with

Cuban saxophonist Paquito D’Rivera beginning in the early 1980s that

best showcased his fiery Latin-tinged style. A versatile player on

both trumpet and flugelhorn, he has recorded in numerous jazz

settings and was a valuable member of Dizzy Gillespie’s United

Nation Orchestra.

As a leader, Roditi has recorded for various labels, including

Green Street (1984’s “Red on Red”), Uptown (“Claudio”), Milestone

(“Gemini Man” and “Slow Fire”), Candid (“Two of Swords” and the live

“Milestones”), Reservoir (“Free Wheelin’: The Music of Lee Morgan,”

“Samba Manhattan Style” and “Double Standards”), Mons (with the

Metropole Orchestra) and RTE (“Jazz Turns Samba” and “Claudio, Rio

and Friends”).

His solo work “Symphonic Bossa Nova” with Ettore Stratta and the

Royal Philharmonic, earned Roditi a Grammy nomination in 1995.

Roditi plans to continue to blend the two musical forms he loves.

As he told Stan Woolley in Jazz Journal International, “I am a

Gemini. I was born in one country and live in another but I love

them both, and both kinds of music, too.”

The following excerpts are from an interview by Gregory F. Pappas

April 7, 2001, in San Antonio, Texas:

Pappas: If you had to choose a few bars or a cut

representative of your music which would it be?

Roditi: A tune that I wrote called “Gemini Man” represents

best the way I feel about samba mixed with jazz. It is from an album

I also did by that name.

Pappas: What musicians would you like to play with (alive or dead)

and have not had a chance?

Roditi: I guess I have been very fortunate to play with

most of them: Raul De Souza (living now in France), Slide Hampton,

Edsel Machado (I was in his band before coming to the U.S.), Dom Um

Romao, McCoy Tyner (who even recorded some of my tunes) and Horace

Silver. I really wanted to play with Art Blakey and I talked with

him once. He asked me for my phone number but nothing came about.

Pappas: Are there any particular young musicians that you

think deserve wider recognition?

Roditi: There is a Brazilian piano player called Helio

Alves. He plays fantastic. Another one of the few that knows both

the Brazilian and Afro-Cuban tradition.

Pappas: You do travel a lot.

Roditi: Yes! You cannot survive if you stay put. I go to

Europe quite a bit. I have different groups that I play with,

sometimes in Holland but mostly in Germany. I wish I did not have to

travel so far and had more opportunities in the USA.

Pappas: Historically the most famous combination of

Brazilian with jazz is bossa nova. But are there other combinations

worth mentioning? I notice that there is something “harder” about

the approach to Brazilian jazz of musicians like Dom Um Romao, Airto

Moreira, Hermeto Pascoal and you.

Roditi: Let me explain to you what happen in Brazil in the

late ‘50s and early ‘60s. When I moved to Rio in 1964 (from a town

in the interior) it was the height of the bossa nova period. A

record label from Brazil called Musidisc issued in Brazil the entire

Pacific Jazz catalog, with artists like Chet Baker, Bud Shank and

Gerry Mulligan. Their LPs were available and cost much less than the

imported records. That is why cool jazz had such a direct influence

in that period, at least on bossa nova. Bossa was music that

belonged primarily to singers, guitar players, piano players and

composers. But at that time something else happened that I saw first

hand but you never hear about in the US. The guys that were playing

saxophone, trumpet, drums and trombone were mostly playing what we

called samba jazz. In other words, what you are calling a harder

approach was played there in the ‘60s. There were musicians that

grew up near the Favelas, like Edison Machado, that also loved Elvin

Jones and Art Blakey. They had to play hard!

top

|

Concert

Review

Scheps-Brock

Quintet sets house on fire

|

By Tom Ineck

It is unfortunate that the Rob Scheps/Zach Brock Quintet is not a

household

name because they play like a house on fire! It is unfortunate that the Rob Scheps/Zach Brock Quintet is not a

household

name because they play like a house on fire!The quintet made its

Lincoln debut Jan. 22 at P.O. Pears, which has been the scene of

many a fiery jazz performance in the last couple of years, thanks to

the underwriting support of the Berman Music Foundation and

the weekly jazz programming managed by Arts Incorporated.

There is nothing conventional about Scheps’ approach to jazz, and

that makes his music very exciting. The oldest member of the quintet

by nearly a decade, he shepherds his younger sidemen through the

complex changes while allowing them ample freedom to improvise. What

results is a captivating performance capable of riveting the

attention of even the most jaded jazz fan and holding spellbound the

dozens of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln jazz history students

who frequent P.O. Pears, notebooks in hand.

An

Oregon native, Scheps has lived and worked in Boston and New York

City, as well as performing worldwide with artists as diverse as the

Gil Evans Orchestra, trumpeters Clark Terry, Arturo Sandoval, Eddie

Henderson and Terumasa Hino, trombonist Roswell Rudd, singers Mel

Torme, Dianne Reeves and Nancy King, bandleaders Buddy Rich and Mel

Lewis, organist Jack McDuff and avant jazz legends Sam Rivers, Muhal

Richard Abrams, Henry Threadgill and Julius Hemphill. An

Oregon native, Scheps has lived and worked in Boston and New York

City, as well as performing worldwide with artists as diverse as the

Gil Evans Orchestra, trumpeters Clark Terry, Arturo Sandoval, Eddie

Henderson and Terumasa Hino, trombonist Roswell Rudd, singers Mel

Torme, Dianne Reeves and Nancy King, bandleaders Buddy Rich and Mel

Lewis, organist Jack McDuff and avant jazz legends Sam Rivers, Muhal

Richard Abrams, Henry Threadgill and Julius Hemphill.

Co-leader Brock, 29, draws on a broad tradition of jazz violin,

from Johnny Frigo to Stephane Grappelli and even fusion pioneers

Jean-Luc Ponty and Jerry Goodman. Born in Lexington, Ky., he pursued

his musical training in Chicago. For the band’s Lincoln appearance,

he brought along a couple of talented young Windy City musicians,

pianist Jordan Baskin, 24, and bassist Matt Ulery, 22. Rounding out

the quintet was drummer Morgan Childs, also 22, whom Scheps

recruited in Vancouver, B.C.

Brock’s

piece “Mr. Shah” kicked off the proceedings with an irresistibly

clever funk riff, over which Scheps superimposed an extended tenor

sax solo, with the rhythm section comping like veterans. The

composer also took a solo on his five-stringed instrument, a

physical display of pyrotechnics that was, at the same time,

disciplined in its clean lines and melodic ideas. Brock’s

piece “Mr. Shah” kicked off the proceedings with an irresistibly

clever funk riff, over which Scheps superimposed an extended tenor

sax solo, with the rhythm section comping like veterans. The

composer also took a solo on his five-stringed instrument, a

physical display of pyrotechnics that was, at the same time,

disciplined in its clean lines and melodic ideas.

"First Morning at the Tower” was composed by bassist Ulery,

inspired by a visit to Italy. It was constructed on a complex melody

line that worked well as a basis for solos statements by Scheps on

tenor, Baskin on keys and Brock on violin. “Olivia’s Arrival” had

the familiar sound of a standard, but was in fact a little-known

tune by baritone saxophonist Gary Smulyan. Scheps and Brock

displayed a fine sensitivity in their harmonized lines, the two

instruments blending surprisingly well.

For his composition “New Homes,” Scheps switched to flute, an

instrument

closer to the violin’s range. Beginning at mid-tempo, the tune

accelerated as Scheps and Brock joined in a unison line, leading to

a flute solo with Baskin first comping on keys then segueing into a

full-blown solo. Brock also took another masterful, confident solo. For his composition “New Homes,” Scheps switched to flute, an

instrument

closer to the violin’s range. Beginning at mid-tempo, the tune

accelerated as Scheps and Brock joined in a unison line, leading to

a flute solo with Baskin first comping on keys then segueing into a

full-blown solo. Brock also took another masterful, confident solo.

Scheps again introduced an obscure tune with much merit. It was

Joel Weiskopf’s blazing “Tuesday Night Prayer Meeting,” a subtle

reference to the Charles Mingus swinger “Wednesday Night Prayer

Meeting.” It was a tightrope-walking showcase for Scheps on tenor

and Brock on violin, first locked in unison and then in successive

solos. Baskin joined the fray as all three took solos behind Childs’

skillful drum breaks.

During

the break between sets, Scheps told me they like to keep the

audience guessing, sometimes alternating between the music of Cole

Porter and Nirvana. Neither of those extremes was heard that

evening, but the quintet did launch into the second set with Ornette

Coleman’s “Happy House,” a tune not heard every day. It allowed

Scheps to play “outside” on tenor sax and for Brock to show his

pizzicato skill, plucking the violin like a rock guitar. During

the break between sets, Scheps told me they like to keep the

audience guessing, sometimes alternating between the music of Cole

Porter and Nirvana. Neither of those extremes was heard that

evening, but the quintet did launch into the second set with Ornette

Coleman’s “Happy House,” a tune not heard every day. It allowed

Scheps to play “outside” on tenor sax and for Brock to show his

pizzicato skill, plucking the violin like a rock guitar.

Baskin contributed the lovely “Searching for Solace,” which had a

waltz-like lilt. Scheps, on flute, again joined harmonies with

Brock. Scheps introduced the ballad “Crestfallen,” saying that he

wrote it in Nebraska City, where the band had played the previous

night. Brock took the lead, and turned in a gorgeous reading of the

tune. “Little Jewel,” also by Scheps, featured a soulful piano

introduction and another great tenor solo by the composer.

“Common

Ground,” a track from Brock’s CD “The Coffee Achievers,” was another

twin-voiced piece featuring Scheps on tenor and Brock on violin.

Finally, Scheps pulled out all the stops for “The Cougar,” first

working out on the tenor sax, then combining the flute mouthpiece

and the sax body to take a soaring solo on the “saxaflute.” “Common

Ground,” a track from Brock’s CD “The Coffee Achievers,” was another

twin-voiced piece featuring Scheps on tenor and Brock on violin.

Finally, Scheps pulled out all the stops for “The Cougar,” first

working out on the tenor sax, then combining the flute mouthpiece

and the sax body to take a soaring solo on the “saxaflute.”

It was the kind of over-the-top antic that few musicians could

pull off convincingly. Judging from the response, the Scheps-Brock

quintet convinced everyone in the audience.

top

|

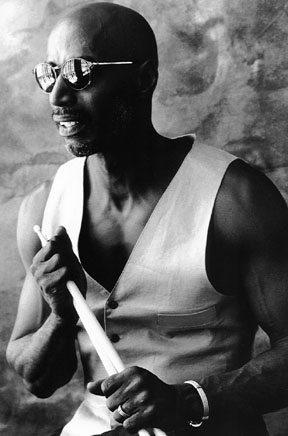

Artist Interview

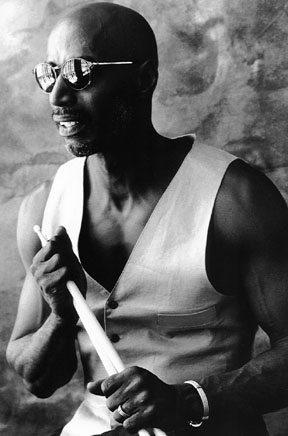

T.S. Monk

champions jazz as popular music

|

By Tom Ineck

There is no more articulate and passionate advocate of jazz as

popular music

than T.S. Monk, the distinguished drummer and son of Thelonious

Monk. As chairman of the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz, he also

is the keeper of the flame, a responsibility that he takes very

seriously. There is no more articulate and passionate advocate of jazz as

popular music

than T.S. Monk, the distinguished drummer and son of Thelonious

Monk. As chairman of the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz, he also

is the keeper of the flame, a responsibility that he takes very

seriously.

When Monk and his band were scheduled to appear in Lincoln a

couple of months ago, I arranged a live radio interview to take

place during “NightTown,” my weekly jazz program on KZUM Community

Radio. Despite slow ticket sales that forced the concert’s

cancellation, Monk wanted to go ahead with the phone interview.

Familiar with his eloquence from an interview we had done for

publication in the Lincoln Journal Star more than a decade ago, I

jumped at the chance to chat with him again.

Several recent developments in Monk’s career, including the new

CD “Higher Ground” and the launch of Thelonious Records (and the

website www.monkzone.com) for his own recordings and those of his

father, provided plenty of subject matter for our 45-minute, on-air

conversation. Monk, as always, proved an easy interview.

On his fresh approach to Ray Bryant’s “Cubano Chant” (from

“Higher Ground”) and other standards that he has recorded: “The

great thing about the standard compositions is that they really

provide a framework that’s intergenerational, that’s chronologically

neutral in many, many ways, so it allows you to revisit a

composition and really bend it and twist it. Because it’s a

standard, it generally means that it has some fundamental, bedrock

elements that you really can’t do without. As long as they’re

incorporated, you still have the same tune.”

On the timeless accessibility of good music: “That doesn’t

change from genre to genre or era to era. Those elements that make a

hit tune, so to speak, are the same for everyone. It boils down to a

haunting melody that you will always remember, a great groove, and

generally, some harmonics that make you think and give you some

texture.”

On the importance of knowing jazz history and developing a

jazz vocabulary: “Jazz is a continuum, but in order for it to

continue, one must constantly revisit what’s gone before you, so

that you know that you’re in some sort of new territory, or at least

in a new region. Often, at least to my ear, a lot of the younger

jazz musicians don’t learn tunes the way we used to have to learn

tunes. You had to know 300 tunes, and what that does for the jazz

musician is to increase your vocabulary. You have to revisit the

music that’s preceded you in order to maximize your vocabulary, so

you can then go into the future and have something new to say.”

On the importance of working in the consistent context of a

band: “That’s key, in terms of finding your creative center. A

jazz musician’s only true home is in a band, and if you look at the

great musicians throughout the history of jazz, every single one

came from a great band. You can trace them back, whether it’s Bird

and Miles back to the Jimmie Lunceford band or you’re tracing

Coltrane back to the Miles Davis or the Monk band or you’re tracing

Monk back to the Coleman Hawkins band. We develop a vocabulary, and

that vocabulary is developed in order for us to converse. If one is

to truly converse properly, you have to talk to each other on a

continuous basis. You can’t have brief, intermittent conversations.

As you have those conversations, you develop ideas. It’s the same as

it is for the man on the street. It’s the same as it is in all the

other quarters of society. So, if you listen to what is played by

Miles with Red Garland, Jimmy Cobb and Paul Chambers, those records

were the result of many, many conversations over many, many nights.

The only way you can do that is by keeping a band together. The

great entrepreneurs in the recording industry years ago, people like

Alfred Lion, understood this clearly. That’s why you saw those bands

stick together. You saw Monk and (Charlie) Rouse together for years

and years. You saw Miles and Coltrane. You saw Wayne Shorter and Joe

Zawinul in Weather Report. You saw Miles and Herbie Hancock and Tony

Williams and Wayne Shorter and Ron Carter. Those are all creative

cauldrons. It does make a strong case for the continuum of a

creative process when musicians can play together regularly. When

you look at the (current) landscape of jazz, there aren’t many bands

that stick together. That’s had a negative effect on the overall

creative movement in the music.”

On the emergence of Wynton Marsalis in the early 1980s and the

“jazz star:” “The jazz recording industry got a little enamored

with the concept of what they might have misconstrued as ‘instant

stardom.’ As a consequence of that, we saw the jazz labels go on a

quest for about 15 years to see who could find the youngest, most

unknown ‘next,’ and it didn’t quite work out that way because that’s

a blueprint that we’ve taken from pop music and overlaid it on jazz.

It doesn’t work for jazz because it restricts the concept of artist

development, and artist development is the most critical factor in

the development of a jazz recording artist. In today’s recording

environment, my father, Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy and maybe even

John Coltrane in his latter years would not have gotten a recording

deal. They were too different. They were doing exactly what they

were supposed to do, and right now the industry has gotten an

attitude of sameness. The bedrock of the music is individuality.”

On Thelonious Records and its mission: “It’s originally my

father’s dream, in that he recorded himself at home and other people

recorded him in all kinds of clandestine ways. Jazz musicians

pioneered the concept of the home production, the self-contained

production vehicle—I wrote the music, I played the music, I recorded

the music. Thelonious Records is about two things. It’s about the

Monk family, the branding of the Monk family, that is myself and my

father and our music. It’s also about new ideas. I can tell you

realistically that I’m two years away from the first new ideas, in

terms of signing an artist because getting up and running is the

critical thing.”

On the importance of marketing and promoting jazz: “I’m

very old-school, and very P.T. Barnum-oriented and I say, ‘Listen,

I’ve got this six-piece band and it’s baaaaaaaad. It will blow you

out. We will kick your you-know-what.’ That’s how I feel about my

band, and that’s how I feel about jazz in general. Jazz is the one

area in music that has enormous room for growth, and we have to take

advantage of that. We have to learn how to sell our products. We

have a product that has a shelf life that, we now know, can be as

long as 50 or 60 years. We know that we have a marketplace that is

international in scope. The concept of how you actually sell this

music is a little bit of a mystery, even though it seems to sell

year in and year out, at a slow pace. I don’t believe that slow pace

is a function of the art form. I think that slow pace is a function

of the industry, and so I’m looking to change it. If a few other

people get involved, we get that shift in the industry the way

country music had its shift in the ‘80s, the way r&b had its shift

in the ‘90s. I have been offended over the years. First, I was

offended by people who said that you couldn’t teach jazz in an

institution. We’ve been very successful, and in our 18th year, with

the Monk Institute. I got doubly offended by the people who said you

can’t really market jazz because it’s really not for the mainstream.

I think that’s absolutely ridiculous.”

On his concept of “cross-talking” and blending jazz styles:

“The umbrella of jazz is really quite vast, as far as I’m concerned.

Even though every jazz musician that I know is extraordinarily

versatile, I don’t see a lot of versatility being reflected in the

bands. Bands tend to stay in one little niche. Perhaps because I’m a

drummer, and I don’t have a melodic instrument to rest on, I like to

give you a lot of different looks. Although we change genres or

change idiomatically, we don’t change the instruments. That’s what

allows us to cross-talk, so we can please all of the people all of

the time.”

On his father, who died in 1984, and his mother, Nellie, who

died in 2002: “Without Nellie, we would have had no Thelonious

Monk. Nellie and Monk met when he was 17 and she was 12 years old,

and they started dating when she was 17 and he was 22. She

understood his artistry from day one, and she became all things that

one human being can be to another—a lover, a friend, a confidant, a

brother, a sister. Although I miss her incredibly, because not only

was she my mom but I was born on her birthday, I know that she and

Thelonious are together now. That’s the Romeo and Juliet of jazz.

That’s one of the great hookups that you ever had.”

On “Monk in Paris: Live at the Olympia,” a CD and bonus DVD

recently released on Thelonious Records: “Thelonious was really

a live artist. When you speak to people who had the opportunity to

see Thelonious perform live most of them say, ‘I went back and saw

him every night for two weeks,’ because he was the real thing.

Thelonious could play you 20 different solos on the same tune over

20 nights. On these recordings that I have now that we’re going to

be releasing over the next several years, the band is thumpin’. The

band is really swingin’. A lot of listeners are most familiar with

the CBS recordings that he did because those are the clearest, those

are the best recordings, and those probably have the highest

visibility, even more so than the Blue Note and Prestige recordings.

But even on those recordings, you don’t get the energy level that

Thelonious projected. In many ways, you could misconstrue Thelonious

as sort of a laid-back guy. But the reality is that this is the guy

who influenced John Coltrane and Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie and

a whole generation of the greatest who ever lived. And, it was

because he was very exciting. In these recordings that we have with

Thelonious Records, that’s what’s going to come out—how much fun

Thelonious was live. And, when you see Thelonious (on the DVD), then

a lot of the things he played make even more sense.”

On Thelonious Monk’s piano-playing style and philosophy of

“practice”: “Thelonious was a great player. The great piano

player Barry Harris once said to me that there were two players he

knew that he never heard ‘practice.’ They only played. They

‘practiced’ playing. That was Thelonious and his main protégé, Bud

Powell. When I think back, I say, ‘You know what, I never heard my

father play a scale. I never heard him do any of those exercises

that you always hear piano players doing, two-hand scales and all

that kind of stuff. What he would do was sit down at the piano at 10

o’clock in the morning and not stop until 8 o’clock, before he went

to the club at night to play his gig. He would be absolutely

performing.”

top

|

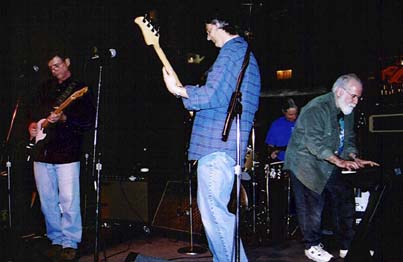

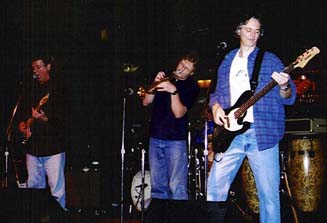

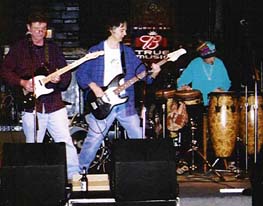

Performance Photo Feature

Jim Jacobi celebrates release of "Get Out!"

|

Veteran “punk rocker” Jim Jacobi had his CD release party Dec. 16 at

the Zoo Bar in Lincoln to celebrate his brand new endeavor, “Get

Out.” All the players on the disc were there to cameo their recorded

performances. Jacobi’s rhythm section, drummer Dave Robel and

bassist Craig Kingery, was joined by Butch Berman, piano; Dr. Dave

Fowler, fiddle; Steve “Fuzzy” Blazek, lap steel; and Charlie Burton

and Carole Zacek, vocals. Also in attendance were Rick Petty,

congas; Phil Shoemaker, guitar; and Brad Krieger, trumpet.

top

Editor’s Note:

At your request, we will mail a printed version

of the newsletter. The online newsletter also is available at this website

in pdf format for printing. Just click here: Newsletter

|

Claudio Roditi, bringing him to Lincoln for a performance with

saxophonist Greg Abate in February 1996. The concert at the

now-defunct 7th Street Loft also featured pianist Phil DeGreg,

bassist Bob Bowman and drummer Todd Strait, all of whom have

maintained close ties with the BMF.

Claudio Roditi, bringing him to Lincoln for a performance with

saxophonist Greg Abate in February 1996. The concert at the

now-defunct 7th Street Loft also featured pianist Phil DeGreg,

bassist Bob Bowman and drummer Todd Strait, all of whom have

maintained close ties with the BMF. It is unfortunate that the Rob Scheps/Zach Brock Quintet is not a

household

name because they play like a house on fire!

It is unfortunate that the Rob Scheps/Zach Brock Quintet is not a

household

name because they play like a house on fire! An

Oregon native, Scheps has lived and worked in Boston and New York

City, as well as performing worldwide with artists as diverse as the

Gil Evans Orchestra, trumpeters Clark Terry, Arturo Sandoval, Eddie

Henderson and Terumasa Hino, trombonist Roswell Rudd, singers Mel

Torme, Dianne Reeves and Nancy King, bandleaders Buddy Rich and Mel

Lewis, organist Jack McDuff and avant jazz legends Sam Rivers, Muhal

Richard Abrams, Henry Threadgill and Julius Hemphill.

An

Oregon native, Scheps has lived and worked in Boston and New York

City, as well as performing worldwide with artists as diverse as the

Gil Evans Orchestra, trumpeters Clark Terry, Arturo Sandoval, Eddie

Henderson and Terumasa Hino, trombonist Roswell Rudd, singers Mel

Torme, Dianne Reeves and Nancy King, bandleaders Buddy Rich and Mel

Lewis, organist Jack McDuff and avant jazz legends Sam Rivers, Muhal

Richard Abrams, Henry Threadgill and Julius Hemphill. Brock’s

piece “Mr. Shah” kicked off the proceedings with an irresistibly

clever funk riff, over which Scheps superimposed an extended tenor

sax solo, with the rhythm section comping like veterans. The

composer also took a solo on his five-stringed instrument, a

physical display of pyrotechnics that was, at the same time,

disciplined in its clean lines and melodic ideas.

Brock’s

piece “Mr. Shah” kicked off the proceedings with an irresistibly

clever funk riff, over which Scheps superimposed an extended tenor

sax solo, with the rhythm section comping like veterans. The

composer also took a solo on his five-stringed instrument, a

physical display of pyrotechnics that was, at the same time,

disciplined in its clean lines and melodic ideas. For his composition “New Homes,” Scheps switched to flute, an

instrument

closer to the violin’s range. Beginning at mid-tempo, the tune

accelerated as Scheps and Brock joined in a unison line, leading to

a flute solo with Baskin first comping on keys then segueing into a

full-blown solo. Brock also took another masterful, confident solo.

For his composition “New Homes,” Scheps switched to flute, an

instrument

closer to the violin’s range. Beginning at mid-tempo, the tune

accelerated as Scheps and Brock joined in a unison line, leading to

a flute solo with Baskin first comping on keys then segueing into a

full-blown solo. Brock also took another masterful, confident solo. During

the break between sets, Scheps told me they like to keep the

audience guessing, sometimes alternating between the music of Cole

Porter and Nirvana. Neither of those extremes was heard that

evening, but the quintet did launch into the second set with Ornette

Coleman’s “Happy House,” a tune not heard every day. It allowed

Scheps to play “outside” on tenor sax and for Brock to show his

pizzicato skill, plucking the violin like a rock guitar.

During

the break between sets, Scheps told me they like to keep the

audience guessing, sometimes alternating between the music of Cole

Porter and Nirvana. Neither of those extremes was heard that

evening, but the quintet did launch into the second set with Ornette

Coleman’s “Happy House,” a tune not heard every day. It allowed

Scheps to play “outside” on tenor sax and for Brock to show his

pizzicato skill, plucking the violin like a rock guitar. “Common

Ground,” a track from Brock’s CD “The Coffee Achievers,” was another

twin-voiced piece featuring Scheps on tenor and Brock on violin.

Finally, Scheps pulled out all the stops for “The Cougar,” first

working out on the tenor sax, then combining the flute mouthpiece

and the sax body to take a soaring solo on the “saxaflute.”

“Common

Ground,” a track from Brock’s CD “The Coffee Achievers,” was another

twin-voiced piece featuring Scheps on tenor and Brock on violin.

Finally, Scheps pulled out all the stops for “The Cougar,” first

working out on the tenor sax, then combining the flute mouthpiece

and the sax body to take a soaring solo on the “saxaflute.” There is no more articulate and passionate advocate of jazz as

popular music

than T.S. Monk, the distinguished drummer and son of Thelonious

Monk. As chairman of the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz, he also

is the keeper of the flame, a responsibility that he takes very

seriously.

There is no more articulate and passionate advocate of jazz as

popular music

than T.S. Monk, the distinguished drummer and son of Thelonious

Monk. As chairman of the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz, he also

is the keeper of the flame, a responsibility that he takes very

seriously.